Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

Donald Trump’s administration has revoked licences for BP and Shell gas projects in Venezuelan waters intended to supply a massive liquefied natural gas plant critical to Trinidad and Tobago’s economy.

The decision marks the latest US move to ratchet up economic and diplomatic pressure on Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s autocratic president, who was sworn in for a third term in January despite widespread evidence of fraud in the July election.

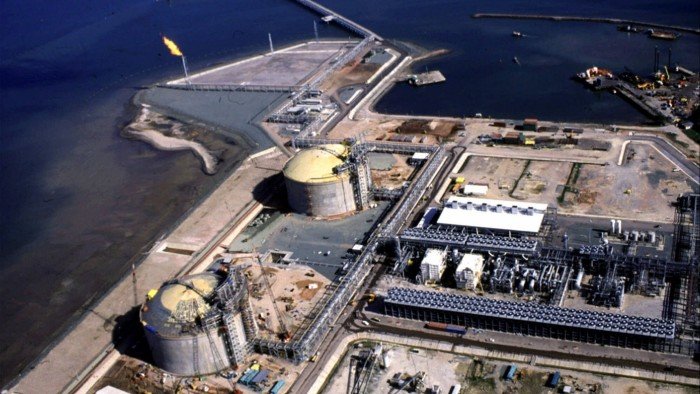

The licences relate to Shell’s Dragon and BP’s Cocuina-Manakin projects, which are joint ventures involving Trinidad and Tobago’s National Gas Company and its government. Both of the development projects would have used existing gas infrastructure owned by both companies in Trinidad and Tobago waters to transport gas to the Atlantic LNG plant on the Caribbean island, in which BP and Shell own stakes.

The projects represented one of the few ways that Venezuela could generate revenue from its vast gas reserves.

The revoking of the licences, which were held by the government of Trinidad and Tobago, marks a setback for BP and Shell, which had sought to expand development into Venezuela’s gas-rich waters. The companies were relying on special licences the previous Joe Biden administration issued that enabled them to operate despite US sanctions against Venezuela’s authoritarian government.

Washington’s action also represents a blow to Trinidad and Tobago’s struggle to supply the Atlantic LNG project, which has idled a fifth of its capacity since 2020 because of shortages of domestic gas.

Stuart Young, the prime minister of the Caribbean island, on Tuesday said the Trump administration had informed his government that both licences were revoked. He said his government would seek to appeal.

Young said: “This does not come necessarily as a surprise, seeing how volatile things are, not only with respect with Venezuela, but what we are seeing for example with the application of tariffs . . . There seems to be a lot of unsettling times in Washington, DC.”

The revocation of the Trinidad and Tobago licences follow similar measures the US has taken against other companies as it seeks to isolate Venezuela.

Last month the US Treasury revoked exemptions to operate in Venezuela for Chevron, Repsol, Eni and Global Oil Terminals, a company owned by Floridian Republican donor Harry Sargeant III. They have been ordered to wind down operations by May 27.

US sanctions prohibit any business with Venezuela’s state-owned oil major Petróleos de Venezuela, though the Biden administration granted exemptions as it tried unsuccessfully to coax Maduro into pro-democracy political reforms.

Maduro on Tuesday night signed an “economic emergency” decree amid escalating sanctions, announcing measures that include suspending municipal tax collection and the “mandatory purchase” of domestic products instead of imports.

“Given the international circumstances and the impact of the trade war on the world and Venezuela, I appeal to the constitutional powers granted to me by this decree to protect all sectors,” Maduro said while signing the document.

LNG is central to Trinidad’s economy, with exports worth $3.6bn in 2023, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity. The Dragon field, the development of which Trinidad and Tobago has said is vital for its energy security, is estimated to contain about 4tn cubic ft of gas reserves. Shell had hoped to begin producing gas by 2026 or 2027 to supply Atlantic LNG.

The US Treasury, the Venezuelan government and BP did not immediately respond to requests for comment. Shell declined to comment.

Francisco Monaldi, a Latin America energy expert at Rice University in Houston, said the revocation of licences for the Trinidadian projects came as a surprise.

“I thought that they would make an exception for these projects as they were not going to be giving any significant amount of money to Maduro in the foreseeable future,” Monaldi said.