- The US Dollar Index ended the week slightly in the red.

- Trump’s “liberation day” keeps global markets on edge.

- The door remains wide open to a global trade war.

A poor second half of the week left the US Dollar (USD) empty-handed, reversing the previous week’s advance despite hitting new three-week tops well north of the 104.00 barrier in the last couple of days, when measured by the US Dollar Index (DXY).

The initial optimism in the Greenback came in response to further tariff threats by the White House, although concerns over how the United States (US) economy might fare in this new scenario of trading tensions eventually hurt sentiment and dragged the index lower.

This choppiness around the US Dollar followed a widespread, mixed performance in US yields. That said, while the short end slipped back to multi-day lows, the belly and the long end of the curve trimmed part of the weekly recovery on Friday, leaving them with modest gains for the week.

Trade turbulence and price pressures

This week, the fervor surrounding US tariffs has reignited following a fresh 25% tariff on US imports of cars and car parts on Wednesday. Yet, it’s important to remember that after a 25% levy hit Mexican and Canadian imports on March 4, President Trump swiftly offered a reprieve—suspending the tariffs on goods under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) until April 2. Meanwhile, an additional 10% tariff on Chinese imports, raising the total to 20%, remains in force.

This topic continues to ignite debates among market participants and global governments alike, all ahead of the dubbed “liberation day” on April 2.

So, what is “liberation day”?

The Trump administration is gearing up for what it calls “liberation day” on April 2, when a new round of tariffs is set to hit. This move is seen as the pinnacle of President Trump’s “America First Trade Policy”—a vision he unveiled with an executive order on his first day in office, aiming to rejuvenate US manufacturing.

Dubbed “the big one” by Mr. Trump, the upcoming tariff announcement hints at measures that could be even more expansive than the recent 25% import levies imposed on vehicles and auto parts just days ago.

In fact, the administration plans to introduce what are known as reciprocal tariffs—taxes on imported goods that match the tariffs other countries have placed on American products. The goal? To correct trade imbalances with nations that export more to the US than they import in return.

The immediate impact of higher import duties is typically a one-off surge in consumer prices, an effect that is unlikely to trigger an instant policy shift by the Federal Reserve (Fed). However, if these trade measures become a long-term fixture or intensify further, producers and retailers could be driven to maintain elevated prices—either due to diminished competition or in pursuit of higher profit margins.

This secondary wave of price hikes might eventually dampen consumer demand, slow economic growth, affect employment, and even pave the way for renewed deflationary pressures. Such outcomes could, in time, force the Fed into more aggressive action.

Navigating a slowing economy and inflation overshoot

Other than the tariff narrative, the recent price action in the US Dollar has been driven by growing speculation about a potential economic slowdown, a sentiment reinforced by lacklustre data and waning market confidence.

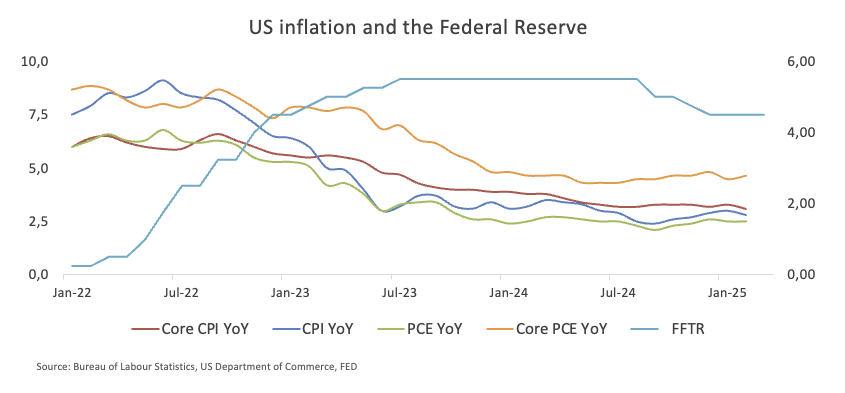

Although inflation still exceeds the Fed’s 2% target, as reflected in both CPI and PCE measures, a strong labor market adds another twist to the narrative.

Ultimately, this mix of factors—along with rising uncertainty over new US tariffs—led the Fed to hold interest rates steady at its March 19 meeting.

Prudence in policy: The Fed’s steady approach to economic challenges

On March 19, the Federal Reserve wrapped up its meeting by keeping the federal funds rate anchored between 4.25% and 4.5%.

Citing heightened uncertainty—from shifting policies to rising trade tensions—the Committee opted for a cautious stance. At the same time, it revised its 2025 forecasts, lowering real GDP growth from 2.1% to 1.7% and nudging inflation expectations up from 2.5% to 2.7%. These adjustments highlight growing worries about a stagflation threat, where slow growth intersects with higher inflation.

During his customary press conference, Fed Chair Jerome Powell reiterated that there is no immediate need for additional rate cuts.

Overall, this week’s commentary highlights a Fed that remains cautious, balancing concerns over tariff-driven inflation, uneven progress toward the 2% target, and the implications of a solid labor market. While some officials foresee rate cuts, the timing and scope remain fluid as policymakers evaluate ongoing economic indicators and trade developments:

Federal Reserve Governor Adriana Kugler noted this week that interest rate policy remains restrictive and appropriately calibrated, while progress toward the Fed’s 2% inflation target has lost momentum since last summer. She described the recent rise in goods inflation as “unhelpful.”

Meanwhile, Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic said he now foresees slower progress on inflation in the months ahead and has revised his forecast for interest rate cuts, expecting only a single quarter-point reduction by year-end. He explained that businesses are likely to pass on upcoming tariff costs and that weaker inflation gains will delay the appropriate path for policy.

Boston Fed President Susan Collins suggested that tariffs will inevitably drive inflation higher in the near term, though the extent of this effect remains uncertain. She emphasised that a short-lived jump in inflation seems more likely than not, but there is still a risk that elevated price pressures could persist. Consequently, she anticipates that the Fed will keep interest rates steady for a longer period.

San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly maintained that two rate cuts this year are still a “reasonable” projection. With the labour market robust, the economy growing, and inflation edging lower, she believes policymakers can wait to reduce rates until they see how businesses adapt to tariff-related costs.

Next on tap for the USD

All eyes are on the labor market data, with March’s Nonfarm Payrolls set to take center stage, followed closely by the ADP report and JOLTs Job Openings. Additionally, the ISM will release its monthly surveys on the manufacturing and services sectors, and, as always, expect lively commentary from Fed officials to spice things up.

Mapping the US Dollar Index

Technically, the US Dollar Index (DXY) is still trading below its key 200-day Simple Moving Average (SMA) at 104.92, reinforcing a bearish outlook.

Buyers appear to have re-entered the market following the recent oversold conditions, but if the rebound continues, we could see the index revisiting the weekly top of 104.68 (March 26), prior to the 200-day SMA. North from here emerges the provisional 55-day and 100-day SMAs, positioned at 106.44 and 106.74 respectively. Beyond that, the index may run into further obstacles at the weekly high of 107.66 (February 28), the February peak of 109.88 (February 3), and ultimately the 2025 top of 110.17 (January 13).

On the downside, should selling pressure gather pace, support levels are expected first at the 2025 bottom of 103.22 (March 11) and then at the 2024 trough of 100.15 (September 27), both preceding the critical 100.00 level.

Momentum indicators present a mixed picture: the daily Relative Strength Index (RSI) has slipped back to the 40 area, lending a more pessimistic tone, while the Average Directional Index (ADX) has eased to around 29, hinting that the current trend could be running out of some steam.

DXY daily chart

Fed FAQs

Monetary policy in the US is shaped by the Federal Reserve (Fed). The Fed has two mandates: to achieve price stability and foster full employment. Its primary tool to achieve these goals is by adjusting interest rates.

When prices are rising too quickly and inflation is above the Fed’s 2% target, it raises interest rates, increasing borrowing costs throughout the economy. This results in a stronger US Dollar (USD) as it makes the US a more attractive place for international investors to park their money.

When inflation falls below 2% or the Unemployment Rate is too high, the Fed may lower interest rates to encourage borrowing, which weighs on the Greenback.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) holds eight policy meetings a year, where the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) assesses economic conditions and makes monetary policy decisions.

The FOMC is attended by twelve Fed officials – the seven members of the Board of Governors, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and four of the remaining eleven regional Reserve Bank presidents, who serve one-year terms on a rotating basis.

In extreme situations, the Federal Reserve may resort to a policy named Quantitative Easing (QE). QE is the process by which the Fed substantially increases the flow of credit in a stuck financial system.

It is a non-standard policy measure used during crises or when inflation is extremely low. It was the Fed’s weapon of choice during the Great Financial Crisis in 2008. It involves the Fed printing more Dollars and using them to buy high grade bonds from financial institutions. QE usually weakens the US Dollar.

Quantitative tightening (QT) is the reverse process of QE, whereby the Federal Reserve stops buying bonds from financial institutions and does not reinvest the principal from the bonds it holds maturing, to purchase new bonds. It is usually positive for the value of the US Dollar.